Emmett Shea

1961

Sassamon Photo

Herve B.

Lemaire Award for Excellence in Education

November

23, 2010

Emmett

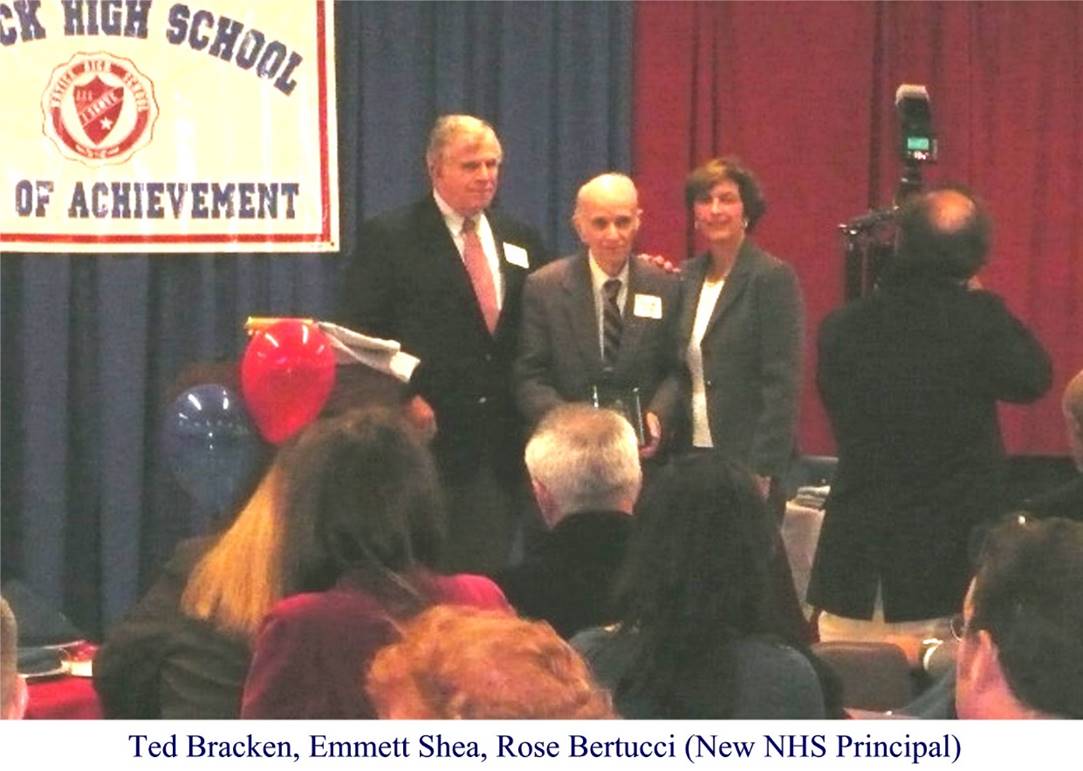

Shea Introduction – by Ted Bracken

We are delighted to open this

evening’s program with the fifth annual Herve B.

Lemaire Award for Excellence in Education. This annual award recognizes a

current or former teacher, coach, or administrator who has had an extraordinary

impact on Natick students. To qualify for selection, a nominee must have served

for a minimum of 5 years at a public school in Natick.

The award is named in memory of Herve Lemaire, to honor and exemplify his exceptional

commitment to the quality of education in Natick. Mr. Lemaire

served the students of this town as a teacher of French and Latin before

becoming vice principal, then principal,

of Wilson Junior High. He served as its principal from 1966 until his

retirement in 1986. During Mr. Lemaire’s tenure as principal, in a

ceremony at the White House, Wilson Junior High was recognized as one of the

top one hundred schools in the United States.

Each year inductees to the Wall of

Achievement have spoken fondly of the influence a particular teacher or coach

has had on their development. It is

therefore fitting that, as part of the annual Wall of Achievement ceremonies,

we also honor the teachers and coaches who most influenced the educational

climate at Natick High School.

Several years ago when writing to nominate

Mr. Shea for this award, I began with some general observations about

great teachers. I would like to recount

each one and then tell a brief story to illustrate how Emmett Shea embodies these qualities.

First,

great teachers are all passionate about their subject matter

The most

common theme in each of the many letters nominating Mr. Shea

is his passion for his subject, which is history and, most especially 20th century European

history with a special emphasis on Russia.

Second,

great teachers are uncompromising in their intellectual values and the pursuit

of truth.

Mr. Shea set high expectations and expected you to meet them. He

taught us that history is not a process of rote memorization of facts and

dates, but an argument-- and he invited us to become participants in that

argument. In Mr. Shea’s

courses, reading original source material was required (e.g., Marx’s Communist

Manifesto, Lenin’s subversive little pamphlet What Is to Be Done?)

And we were always asked to think for ourselves. A case in point was

the paper he assigned that required each of us to select one of the combatant

countries of World War I (Germany,

Austria-Hungary, Serbia, England, France, or Russia) and write a paper that

made the case (with

documentation) for why that country was primarily responsible for starting the

war in 1914. Donald Kennedy, the former president of Stanford, once said that

the purpose of a great education should be to make us feel more comfortable

with ambiguity. Well, by that standard,

Mr. Shea’s assignment provided the opportunity for us

to learn that lesson. To engage in the “argument”

that is history.

Because the high school library was—how

should I put this politely-- a little shy on serious historical literature in

those days, he went out and purchased three copies Sidney Fay’s 1928 tour de

force “Origins of the World War” and put them on reserve for us to

use. I also recall vividly that we were

asked to write a paper on why communism as a political and economic system was

flawed and destined to fail in the end.

Recall now that this was 1960 and Khrushchev was telling America that

Russia would “bury us.” This was heady

stuff for a bunch of 17-year-olds, but we ate it up.

Third,

great teachers exhibit a kind of “spiritual calling” to the work that they do

that goes beyond its being simply a job or even a profession.

The late Dartmouth professor, Ben Pressey, said it best when he wrote: “We teachers all seem

to fail. What we teach is forgotten,

even how we teach is forgotten, and if what we do lasts at all, it lasts by the

spirit. And the spirit springs more from what we are and how we live than what we know or have done.” – what

we are and how we live.

Two years ago in a wonderful Middlesex

News article by sportswriter and NHS grad Len Megliola

about the Lemaire award being given to Coach John Carroll, Billy

Pettingill, NHS class of ’64, said about him: “[he]

was the most inspirational person in my life.

As soon as I met him I knew I wanted to be a coach. I

wanted to be him." I

wanted to be him!

Well, a lot of us also wanted to be Mr. Shea –well, maybe not in every way--maybe keep a little

more of our hair—but to emulate him, to have his passion, his integrity, his

love of the life of the mind.

And

lastly, I have said that the influence of great teachers is much broader and

more far-reaching than even they could possibly imagine.

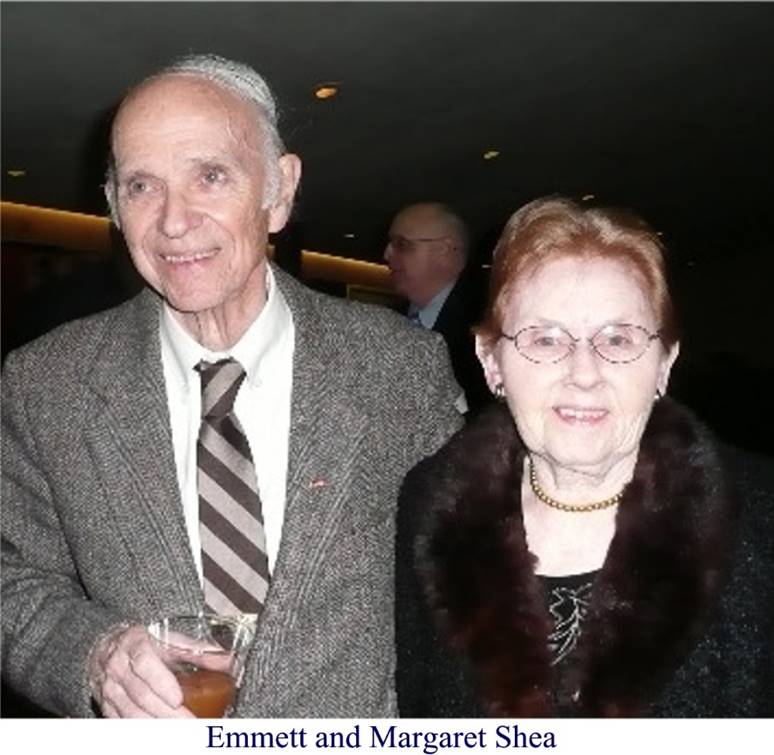

Emmett, I have shared with you how your

passion for the great 20th Century story of the rise of communism

ignited within me a desire when I was a recent college graduate to travel

behind what was then called the “Iron Curtain” to several Eastern Block

counties and how those experiences led to my developing a life-long friendship

with a young communist youth who later became deputy minister of finance in the

Czech Republic after the Velvet Revolution of 1989, and how his two daughters

and my two sons also became friends when they stayed with us here in the US

over two summers. And those continuing

friendships all began in your classroom some 50 years ago. Who could have imagined?

In each of these categories, I can say,

Emmett, as so many others who have also written in their nominating letters,

that you were the best and most influential teacher that I ever had – and that

includes high school, college, and grad school.

Congratulations and, on behalf of the many thousands of students you have

taught both here in Natick and at your various callings in the collegiate

world, from the bottom of my heart, and on behalf of all of the students who

have been fortunate enough to have had you as a teacher, thank you. Or, as they say in Russian, Na zdorovia!

Letters in Support of Emmett Shea’s Nomination For

The Herve B

Lemaire Award for Excellence in Education

Letter Submitted by Ken Gray:

I

am writing to nominate Mr. Emmett Shea, long time

social studies teacher at Natick High, for the Herv Lemaire

Award for excellence in teaching in the Natick public schools. I am a 1961 graduate of Natick High School,

and a 1998 inductee to the Natick High School Wall of Achievement. I took both U.S. history and international

relations courses with Mr. Shea.

I

have long considered myself fortunate to have attended Natick High School. A

major reason was the influence of Mr. Emmett Shea.

As

I look back, and having in the meantime been a high school teacher, guidance

counselor, principal and superintendent of schools, I have come to realize that

he was the commensurate high school teacher.

He both inspired us academically and at the same didn’t look the other

way when a little discipline – now called classroom management – was

necessary. Allow me to elaborate.

I

largely attribute my academic interests, my later career as a college professor

and author, and most importantly my “relative” success as an under-graduate at

Colby College, to the preparation I got from taking Mr. Shea’s

courses. While I was in the college

prep program at Natick High, I cannot say I felt much like I was preparing for

college, until, that is, I was fortunate to have Mr. Shea

for U.S. history and then international relations. It was a different world. There were no textbooks, but instead reading

lists, lectures and discussions. Gone

were the true and false tests and steady diet of films that characterized

previous courses in that wing of the NHS building. It was then I began to realize that perhaps

I was not that slow after all; it was then I developed for the very first time

truly intellectual interests. He taught

us a different way of looking at the world; facts, dates and events suddenly

were viewed not as items to be memorized as if they had some intrinsic value in

of themselves, but as evidence for reaching understanding and conclusions. I wrote my first “real” term papers in his

classes. Suddenly we all wanted to major

in history in college. He took us to

conferences in Boston: we actually gave papers at professional meetings. As I look back, it was so different. I was so lucky; there is no other way to put

it.

Yet

there was another part of Mr. Shea, however, that as

I look back, I think in retrospect impresses me now even more about the

man. He was the guy we were all so

impressed with but who was not above straightening us out when we needed it:

the man who made us grow up as individuals.

I remember one incident in particular.

Student-on-student

harassment was very much the culture in my time at NHS. There were several individuals who in

particular were the brunt of this abuse and I must admit a few of the supposed

“leaders” of our graduating class were among the biggest abusers of these

students. One day Mr. Shea witnessed this

harassment. To us harassment was just

normal life in high school; and I think it fair to say most teachers - at that

time - shared this view. Mr. Shea quickly made it clear to us he did not share this

view: it was not ok. He told us he was ashamed of us. He was mad.

I do not think we had ever seen him mad before.

He informed us that it was time to grow up. That was the end of student

harassment by the “in crowd” of the class of 1961. It suddenly became a very un-cool, immature

thing to do.

Now

an important aspect of this incident was that Mr. Shea

did not have to get involved. The

harassment did not occur in his classroom, he was not on supervision duty; it

was at the end of the day, school was over.

Yet he did get involved, he confronted us, he did not look the other way,

and as a result NHS became a better place and we became much better young

men. That is why I have always been so

grateful to have known Mr. Shea. He was a great teacher, but also a person of

character, a true gentleman, and someone to aspire to be like. That is why I am honored to join those who

are nominating Emmett Shea for the Herv Lemaire Award.

Thank

you for your time and consideration.

Kenneth Gray, NHS Class of 1961

Professor of Workforce Education and

Development

Penn State University

Letter Submitted by Ted Bracken:

Great teachers have certain things in

common.

· They are all

passionate about their subject matter.

· They are

uncompromising in their intellectual values and the pursuit of truth.

· They exhibit a

kind of “spiritual calling” to the work that they do that goes beyond its being

a job or even a profession.

· And their

influence is far broader and far-reaching than even they could possibly

imagine.

In each of these categories, Emmet Shea is a special case.

I have been fortunate to have had three

great teachers in my life: one in high school, one in college (a coach,

actually), and one in graduate school.

The most important of these was the one I had in high school because it

was he who first taught me to think for myself.

That teacher was Emmet Shea.

Great teachers do more than teach. Their influence can be life changing and

affect future generations far beyond the confines of a small classroom so long

ago. Let me explain by telling a story.

Last year, my wife Anne and I, along with

our two sons, 16 and 14, were hosts to a young girl, 17, from the Czech

Republic named Julie Triskova. It was her first trip to America and during

her stay with us in Washington, DC, Matt McDonald, who just happens to be the

son of NHS Wall of Achievement charter honoree, Paul McDonald, took her on a

privately arranged tour of the White House where he worked at the time as

Associate Director of Communications for Policy and Planning. This past summer, Julie was able to exchange

the favor when Matt and his wife Amy were hosted by Julie’s family in her

native city of Prague, while they were on a tour of several Eastern European

countries.

It has been 45 years since I took Emmet Shea’s International Relations class at Natick High School,

but these interlocking connections between the Brackens, the McDonalds, and the

Triskas took root in Mr. Shea’s

International Relations class where I first learned to think critically about

and come to terms with what may be the greatest single historical event of the

20th Century: the rise and (at that time) growing threat of

Communism in world affairs.

To this day I remember clearly some of the

reading list: “The Communist Manifesto,” “What Is to Be Done?”, “To the Finland

Station,” “The Origins of the World War,” “Das Kapital.” These were not text books so typical of the

high school experience, but original works by Marx and Lenin and college level

historical treatises by renowned historians.

And I still remember the term papers: In one, we were randomly assigned

a country (Germany, Austria-Hungary, England, France, or Russia) and were asked

to write a paper that made the case (with documentation) for why that country

was primarily responsible for starting World War I. I also recall vividly that we were asked to

write a paper on why Communism as a political and economic system was doomed to

fail in the end. Recall now that this

was 1960 and Khrushchev was telling America that Russia would “bury us.” This was heady stuff for a bunch of 17-year-olds,

but we ate it up.

So it should come as no surprise that,

after all of that exposure to Russian history and 19th Century

radical political thought, I had a yearning to travel behind the “Iron Curtain”

and see for myself what Mr. Shea had been teaching

about. Emmet Shea

had lit the spark and provoked in me a deep desire to see for myself, first

hand, what a Communist system looked like, felt like, and smelled like. As a result, I went to Czechoslovakia (as it

was known then) for two summers: during the tumultuous years of 1967 and 1968,

to participate in and eventually lead an International Work Camp (sponsored in

the US by the Quakers) in the western mountains of the Czech Republic known as

the Sudetenland (which, Mr. Shea had also taught us,

Hitler had so desperately wanted to make a part of his Third Reich). And it was there that I met another camper: a

young, idealistic, youth by the name of Dusan Triska, whose father was a Communist apparatchik and whose

daughter, Julie, would eventually become friends with my own children 40 years

later.

In an ironic twist that would certainly

amuse, but not surprise Mr. Shea, after the “Velvet

Revolution” in Czechoslovakia that took place shortly after the fall of the

Berlin Wall in 1991, Dusan, who had gotten his Ph.D.

in economics, became Deputy Minister of Finance of the Czech Republic under the

presidency of Vaclav Havel, and was responsible for the creation and

implementation of the voucher system that led to transfer of the Czech economy

from publicly owned to privately owned land, companies, and property. From

Communist to Free Marketer in one generation – an outcome that ol’ Mr. Shea was asking us to

consider so many years before.

This story exemplified the true gift of a

great teacher: the power and influence that his teaching has had on people he

has never known or met.